Who Was Melchizedek? A Houston Pastor Explores the Biblical Mystery

A text message came in last Tuesday from someone who'd been visiting St. John's Presbyterian Church for a few weeks. "Pastor Jon, quick question: Who was Melchizedek?"

I smiled at my phone. There's nothing quick about that question.

We ended up texting back and forth for over an hour, diving into Genesis 14, then Hebrews 7, then into Jewish rabbinic literature. By the end of our conversation, we'd touched on ancient Near Eastern history, the nature of Christ's priesthood, and why some mysteries in Scripture might not have tidy answers.

This is exactly the kind of question we love at St. John's. Not because we have all the answers wrapped up neatly, but because we believe faith grows deeper when we're willing to ask hard questions and sit with mystery.

Melchizedek appears in Scripture like a ghost. He shows up suddenly in Genesis 14, blesses Abraham, receives tithes from him, and then vanishes from the narrative. Centuries later, Psalm 110 mentions him cryptically. Then the book of Hebrews brings him back center stage, using him to explain Christ's priesthood in ways that have puzzled and fascinated theologians for 2,000 years.

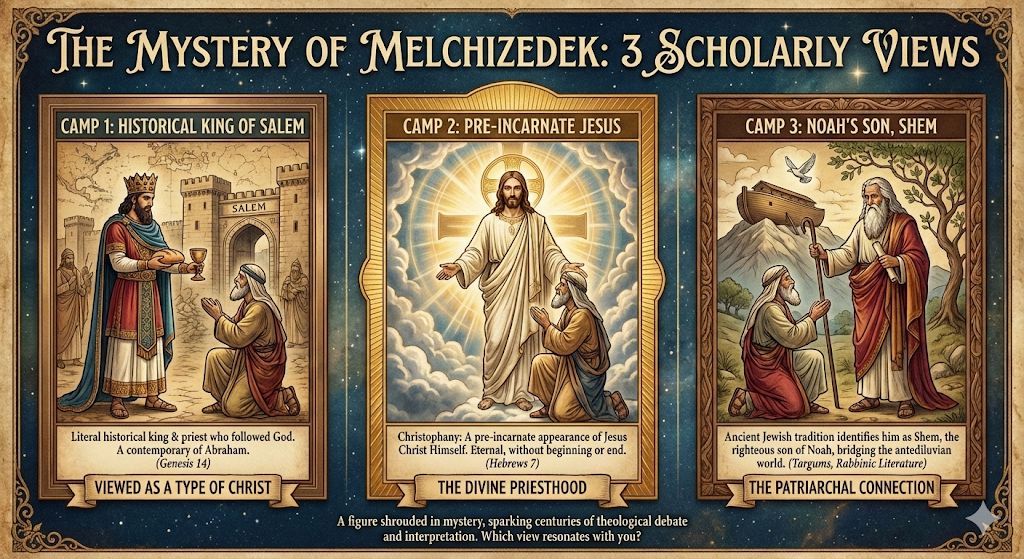

Who was this mysterious figure? Scholars have debated three main interpretations, each with compelling biblical and historical support. Let me walk you through them the way I explained them to my visitor, because understanding Melchizedek isn't just an academic exercise. It's about grappling with how God reveals himself across Scripture and what that means for our faith today.

The Melchizedek Problem: Why This Matters

Before we dive into the three camps, let's understand why Melchizedek causes such discussion in the first place.

He appears in Genesis 14:18-20, right after Abraham (still called Abram at this point) has rescued his nephew Lot from a coalition of kings. Abraham is returning victorious when:

"Then Melchizedek king of Salem brought out bread and wine. He was priest of God Most High, and he blessed Abram, saying, 'Blessed be Abram by God Most High, Creator of heaven and earth. And praise be to God Most High, who delivered your enemies into your hand.' Then Abram gave him a tenth of everything."

That's it. Three verses. But packed into those verses are puzzles that have occupied biblical scholars for millennia:

First, how could there be a priest of "God Most High" before the Levitical priesthood was established through Moses? The law hadn't been given yet. The covenant at Sinai was still centuries away.

Second, why does Abraham, the father of faith, give tithes to this man? Abraham doesn't bow to anyone. Yet here he acknowledges Melchizedek's spiritual authority by giving him a tenth of everything.

Third, where did Melchizedek come from? Scripture gives genealogies for everyone who matters. We know Abraham's father and grandfather. We can trace David's lineage back through Judah to Jacob to Isaac to Abraham. But Melchizedek? He has no father, no mother, no genealogy mentioned. He appears and disappears like morning mist.

When the author of Hebrews picks up this theme centuries later, he makes it explicit: "Without father or mother, without genealogy, without beginning of days or end of life, resembling the Son of God, he remains a priest forever" (Hebrews 7:3).

So who was he? That depends on how you read the clues.

Camp 1: Historical King of Salem

The most straightforward reading takes the text at face value. Melchizedek was a real historical figure, a Canaanite king who ruled Salem (likely ancient Jerusalem) around 2000 BC and who, remarkably, worshiped the one true God.

This view sees Melchizedek as one of those rare individuals outside Israel's covenant line who nevertheless knew and served God. Think of Job, a non-Israelite who was nevertheless "blameless and upright, a man who fears God and shuns evil." Or Jethro, Moses' father-in-law, a Midianite priest who offered sacrifices to the God of Israel.

In the ancient world, knowledge of the true God hadn't been completely lost. The flood was relatively recent history. Noah and his sons had carried forward what humanity had known about God before sin corrupted everything. Some of that knowledge survived in isolated pockets.

Melchizedek, in this reading, represents one of those pockets. A king-priest who maintained worship of "God Most High" (El Elyon in Hebrew) while the rest of Canaan had descended into idolatry. When Abraham arrives in the land, he finds this righteous ruler and recognizes a kindred spirit.

The text says Melchizedek brought out bread and wine, shared them with Abraham, blessed him, and received tithes from him. These were liturgical acts. They established Melchizedek's spiritual authority and Abraham's recognition of it.

Why This View Makes Sense:

Genesis 14 reads like history. It names specific kings, describes a specific military campaign, and places events in a specific geographical context. Taking Melchizedek as a literal historical figure fits the narrative style.

The text never hints that Melchizedek was anything other than human. It calls him "king of Salem" and "priest of God Most High," the same way it identifies other historical figures by their roles and locations.

When Hebrews 7 says Melchizedek was "without father or mother, without genealogy," this view understands that as a literary observation, not a literal description. Scripture simply doesn't record his lineage because he wasn't part of Israel's covenant line. The silence about his origins is significant theologically, but it doesn't mean he had no parents.

The Type of Christ Theme:

This interpretation sees Melchizedek as a "type" of Christ. That's theological language for a person or event in the Old Testament that foreshadows something greater in the New Testament.

Just as Melchizedek was both king and priest (a rare combination), so Christ is both King and High Priest. Just as Melchizedek's priesthood existed before the Levitical order and therefore transcended it, so Christ's priesthood is superior to the old covenant priesthood. Just as Abraham, the great patriarch, honored Melchizedek by giving him tithes, so the entire old covenant order points forward to and honors Christ.

The author of Hebrews develops this typology extensively in chapters 5-7, arguing that Christ is "a priest forever, in the order of Melchizedek" (Hebrews 5:6). He's not from Aaron's line. He doesn't serve in the earthly temple. His priesthood is of a different and superior order, one that Melchizedek mysteriously foreshadowed.

This view is probably the most common among Protestant scholars and fits well with Reformed theology's emphasis on seeing Christ throughout Scripture. At St. John's, we often preach from an understanding that the whole Bible tells one unified story of God's redemption, and typology is one way the Old Testament points forward to that fulfillment in Jesus.

Camp 2: Pre-Incarnate Jesus (Christophany)

The second view takes a more dramatic approach. What if Melchizedek wasn't just a type of Christ, but actually was Christ in a pre-incarnate appearance?

This interpretation sees Melchizedek as a Christophany, a visible manifestation of God the Son before his birth in Bethlehem. Just as Christ appeared to Abraham at Mamre (Genesis 18), wrestled with Jacob at Peniel (Genesis 32), and appeared to Joshua as "commander of the army of the Lord" (Joshua 5:13-15), so he appeared to Abraham as Melchizedek, king of Salem.

The Biblical Case:

Advocates of this view point to several striking details in Hebrews 7:

"Without father or mother, without genealogy, without beginning of days or end of life, resembling the Son of God, he remains a priest forever."

These descriptions, they argue, go beyond simple silence about Melchizedek's origins. They describe attributes that could only be true of a divine being. No human has "no beginning of days or end of life." No created being is "without father or mother" in an absolute sense. Only God himself fits these descriptions.

The phrase "resembling the Son of God" could be translated "made like the Son of God." What if it's not that Melchizedek resembles Christ, but that this appearance was specifically designed to reveal Christ's eternal priesthood?

Moreover, the name "Melchizedek" means "king of righteousness," and "Salem" means "peace." These aren't just coincidental names. They're titles that describe Christ's character and work: he is our righteousness and our peace.

The Eternal Priesthood Theme:

This view emphasizes that Melchizedek's priesthood is described as eternal: "he remains a priest forever." If Melchizedek was simply a historical figure who died like all humans, in what sense does he "remain a priest forever"?

The Christophany interpretation answers: because Melchizedek was Christ, his priesthood truly is eternal. He served as priest in Abraham's time (though without the ceremonial law, which wouldn't come until Sinai), and he serves as our High Priest now, having offered himself as the perfect sacrifice.

Why Some Find This Compelling:

For many Christians, especially those in charismatic and some evangelical traditions, this view makes the Melchizedek passages explode with meaning. It's not just that Christ's priesthood is like Melchizedek's. Christ was Melchizedek. The eternal Son of God has always been our priest, even before the incarnation.

This interpretation also solves the puzzle of how Melchizedek could have "no beginning of days or end of life" in any literal sense. If he was a theophany, these descriptions are simply true.

The Challenges:

The main objection is that Genesis 14 gives no hint that Melchizedek was anything other than human. He's called "king of Salem," he brought out physical bread and wine, and he's listed alongside other historical kings in a narrative that reads like straightforward history.

Additionally, if Melchizedek was Christ, why does Hebrews 7:3 say he "resembles" the Son of God? Wouldn't it be more natural to say he "was" the Son of God?

Still, this view has persisted through church history and continues to have thoughtful advocates who find it both biblically defensible and spiritually enriching.

Camp 3: Shem, Noah's Son (The Patriarchal Connection)

The third major interpretation comes primarily from ancient Jewish tradition and might surprise modern readers. According to rabbinic literature and the Targums (Aramaic translations and interpretations of the Hebrew Bible), Melchizedek was actually Shem, Noah's righteous son.

The Chronological Case:

This view does the math. According to Genesis 11, Shem lived 600 years total. He was 100 when the flood ended (Genesis 11:10) and lived another 500 years after that.

Abraham was born 292 years after the flood (you can calculate this by adding up the genealogies in Genesis 11). The events of Genesis 14, when Abraham was about 75-80 years old, would have occurred roughly 370 years after the flood.

That means Shem was still alive. In fact, according to the chronology, Shem outlived Abraham by 35 years.

The Tradition:

Jewish interpretative tradition, especially in the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan and various midrashic sources, explicitly identifies Melchizedek as Shem. This wasn't a fringe theory. It was widely held in rabbinic Judaism and made perfect sense within their understanding of the patriarchal period.

Why would Shem be called "Melchizedek" (king of righteousness) rather than his given name? Jewish tradition suggests it was a title reflecting his role. As the righteous son through whom God's covenant line continued after the flood, and as a priest who maintained the true worship of God, "king of righteousness" was an appropriate designation.

Salem (Jerusalem) becomes significant in this reading as a place where Shem established worship of the true God. The city that would later house the temple and become the center of Jewish worship had ancient roots as a place where Noah's righteous son served as priest.

The Bridging Figure Theme:

This interpretation sees Melchizedek/Shem as a crucial link between the pre-flood and post-flood worlds. Shem had actually lived before the flood, in the time when patriarchs lived for centuries and the world was young. He carried the knowledge and worship of God through the catastrophic judgment and into the new world.

When Abraham meets Melchizedek, he's meeting someone with a direct connection to Noah and even to the world before sin had fully corrupted creation. The bread and wine, the blessing, the receiving of tithes, all take on added significance as gestures connecting Abraham to the ancient patriarchal worship that stretched back to the beginning.

Why This View Persists:

For those familiar with Jewish interpretative tradition, this view has the weight of ancient interpretation behind it. The rabbis who suggested it weren't engaging in wild speculation. They were working from the biblical chronology and from traditions that may have been passed down orally from earlier generations.

It also elegantly solves the mystery of how there could be a "priest of God Most High" before the Levitical priesthood. If Melchizedek was Shem, he was a direct link to Noah, who built an altar and offered sacrifices after the flood. The priesthood wasn't invented at Sinai. It existed from the earliest days of humanity, with fathers serving as priests for their families, and righteous patriarchs serving as priests for the emerging people of God.

The Challenges:

The main difficulty is that Genesis 14 never hints at this identification. If Melchizedek was Shem, why doesn't the text say so? Why use a different name when Scripture is usually careful to connect people to their lineage?

Additionally, while the chronology makes it possible that Shem was alive during Abraham's life, that doesn't necessarily mean he was Melchizedek. Lots of people were alive then who could have been righteous leaders.

Still, this interpretation has substantial historical pedigree and shows how Jewish scholars wrestled seriously with the Melchizedek mystery long before Christian theologians picked it up.

What Do We Do with Mystery?

Here's what fascinates me about the Melchizedek question: faithful, intelligent, Bible-believing Christians have held all three of these views throughout church history. Each interpretation has biblical support. Each has theological depth. Each enriches our understanding of Christ's priesthood in different ways.

So which one is right?

Maybe that's the wrong question.

At St. John's Presbyterian Church here in Houston, we're part of a tradition that takes Scripture seriously without claiming we have every answer figured out. The Reformed tradition, going back to John Calvin and the other Reformers, has always emphasized both the clarity of Scripture on essential matters and the humility to acknowledge mystery in less essential areas.

The gospel is clear: Christ died for our sins, rose from the dead, and offers salvation to all who believe. That's non-negotiable, clearly taught, and essential to faith.

But who exactly was Melchizedek? That's a fascinating puzzle, worthy of study and discussion, but not something we need to divide over or insist on a single interpretation.

Why We Ask These Questions

The person who texted me wasn't just curious about an obscure biblical character. They were learning to read Scripture carefully, to notice details, to ask good questions. They were discovering that the Bible rewards close attention and that mystery is part of faith.

This is the kind of Bible engagement we encourage in our

Sunday morning Bible Study at St. John's. We meet at 9:30 AM, before our 11:00 worship service, and we work through Scripture together. Sometimes we reach firm conclusions. Sometimes we sit with questions. Always we're digging deeper into God's Word.

The Christian faith isn't intellectual laziness dressed up in religious language. It's not checking your brain at the door and accepting everything without question. True faith engages the mind fully, asks hard questions, and isn't afraid of mystery.

The Apostle Paul put it this way: "For now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known" (1 Corinthians 13:12).

We don't have perfect knowledge now. We see dimly. But we keep looking, keep studying, keep asking questions, because we believe God reveals himself through Scripture and rewards those who seek him diligently.

The Presbyterian Approach to Biblical Mystery

One of the things that drew me to Presbyterian ministry was our tradition's commitment to both intellectual rigor and spiritual depth. We don't have to choose between the mind and the heart. We don't have to pretend questions don't exist or that faith requires ignorance.

The Westminster Confession of Faith, which guides Presbyterian theology, puts it beautifully: "All things in Scripture are not alike plain in themselves, nor alike clear unto all; yet those things which are necessary to be known, believed, and observed, for salvation, are so clearly propounded and opened in some place of Scripture or other, that not only the learned, but the unlearned, in a due use of the ordinary means, may attain unto a sufficient understanding of them."

In other words, Scripture is clear where it needs to be clear. The path to salvation is plain. But not everything is equally plain, and that's okay. God has given us minds to think, hearts to believe, and a community of faith to work through questions together.

When you worship with us at St. John's, you'll find a congregation that loves Scripture and takes it seriously. You'll also find people who aren't afraid to say "I don't know" or "I'm still working on that." We're 250 members strong, averaging about 75 in Sunday worship, and we've created a community where asking questions is encouraged, not feared.

How This Shapes Our Faith

The Melchizedek mystery isn't just an academic puzzle. It shapes how we understand Christ's work and our relationship with God.

Whether Melchizedek was a historical king who foreshadowed Christ, a pre-incarnate appearance of Christ himself, or Shem carrying forward the ancient priesthood, the theological point is the same: Christ's priesthood is eternal, superior to the old covenant system, and sufficient for our salvation.

Hebrews 7 uses Melchizedek to show that Jesus isn't just another in a long line of priests. He's the ultimate priest, the one all others pointed toward. He didn't inherit his priesthood through family lineage (he wasn't from the tribe of Levi). He received it "on the basis of the power of an indestructible life" (Hebrews 7:16).

That's what matters most. Not solving every historical puzzle, but grasping the theological truth: we have a High Priest who lives forever to intercede for us, who offered himself as the perfect sacrifice, and who gives us direct access to God.

Community That Welcomes Questions

If you've beenlooking for a church in Houston where you can ask hard questions without getting easy answers, St. John's Presbyterian might be your place.

We're not a megachurch. We don't have light shows or coffee bars or programs for every demographic. What we have is a community that gathers around Scripture, takes faith seriously, and isn't afraid to wrestle with the text.

OurBible study groups meet throughout the week. Some focus on working through books of the Bible systematically. Others tackle specific theological topics. All of them create space for questions, discussion, and genuine exploration of what we believe and why.

This is what I love about Presbyterian polity and theology. We believe God speaks through Scripture, but we also believe God gave us minds to use and a community to think with. We don't dictate interpretations from the pulpit and expect blind acceptance. We teach, discuss, reason together, and trust the Holy Spirit to guide us into truth.

An Invitation to Explore

The person who texted me about Melchizedek has continued coming to St. John's. They've joined our Sunday Bible Study. They're working through questions about faith, Scripture, and what it means to follow Jesus in Houston in 2026 and beyond.

Their question about Melchizedek wasn't just about solving a biblical puzzle. It was about finding a community where questions like that are welcomed, where faith engages the mind, and where mystery is seen as part of the journey rather than a problem to solve.

Maybe you have questions like that too. Maybe you've been visiting churches and feeling like you have to check your brain at the door, or that asking questions marks you as someone with weak faith.

That's not how we see it. Questions are signs of engagement, curiosity, and a desire to go deeper. The people asking the best questions in our Bible studies are often those most serious about their faith.

We meet at 5020 West Bellfort Avenue, right in the Meyerland area of southwest Houston. Sunday morning Bible Study starts at 9:30 AM, worship is at 11:00 AM. Come join us some Sunday. Bring your questions. Bring your curiosity. Bring your desire to explore faith that engages both heart and mind.

We might not solve every mystery. We probably won't definitively answer who Melchizedek was (though we'll have a great discussion about it). But we'll explore Scripture together, grow in faith together, and discover that mystery isn't the enemy of faith but often its companion.

Call us at 713-723-6262 or visit stjohnspres.org to learn more. Whether you're wrestling with questions about Melchizedek, wondering what Presbyterians believe, or just

looking for authentic Christian community in Houston, we'd love to have you join us.

Because faith that asks questions is faith that's alive, growing, and real. And that's the kind of faith we're cultivating at St. John's Presbyterian Church.

Peace,

Pastor Jon Burnham

Pastor Jon serves St. John's Presbyterian Church in Houston, where he helps people explore the depths of Scripture and discover faith that engages both heart and mind. Whether you're brand new to Christianity or have been following Jesus for decades, you're welcome to join our community as we worship, study, serve, and grow together.